About Rachael Que Vargas

The power of fire and the strength of steel fused in elemental elegance to create sculptural fine art reborn from the ashes of industry.

I make sculpture from scrap industrial steel, cutting by hand with a plasma torch at 45,000° Farenheit. That’s 4.5 times as hot as the surface of the Sun or the Earth’s core.

I make sculpture from scrap industrial steel, cutting by hand with a plasma torch at 45,000° Farenheit. That’s 4.5 times as hot as the surface of the Sun or the Earth’s core.

My Sculptural Firebowls are intended to have an immediate visual appeal as well as providing a story, meaning, and social interaction. They offer an opportunity to gaze into the fire and connect with the human questions that have enticed every imagination since we first gathered around a captive flame over a million years ago.

I created the first Great Bowl O’ Fire on May 30, 2005. I had no idea at the time that it would become the work I was most known for. In the years since I created the first Great Bowl O’ Fire, my art has set the world aflame— I’ve shipped over 2000 Sculptural Firebowls to all 50 states and over 20 countries. Look here for a list of firebowls you can visit, such as SouthEast Porch in Bryant Park, Sandals, Montego Bay, and the Sheraton Waikiki’s Rumfire bar.

My Sculptural Firebowls have been widely covered in books, magazines, newspapers, radio and television. HGTV and DIY Network frequently feature my work on their shows and I’ve been featured in both the Business and Home sections of the New York Times.

As Gabriel Guzman writes in

The Daily Book of Art:

“Who would have thought that a bowl of fire could be so beautiful? Hand-cut out of recycled steel, these bowls combine sculpture and function to create unique works of art with industrial flair that provide warmth and an exciting centerpiece for events. When in use, the flame-like edges of these bowls cast mesmerizing shadows that dance across the ground, acting as part of the art.”

FROM POETRY TO PATTERN—HOW I GOT THERE

I’ve been a professional visual artist since 1995, and have made my living as an artist full-time since 2000. On the way to a successful art career I’ve been a poet and writer, a print and web designer, illustrator, industrial designer, musician, teacher, actor and set designer.

I find that each new medium, motif or material sharpens both my critical thinking and my physical skills. The fifteen years I spent pursuing a poetry career had a direct effect on how I deal with subject matter, narrative, meaning and nuance as a visual artist. The structure and theory I learned as a musician applies directly to my use of pattern, rhythm, lyricality and syncopation in metalwork.

I find that each new medium, motif or material sharpens both my critical thinking and my physical skills. The fifteen years I spent pursuing a poetry career had a direct effect on how I deal with subject matter, narrative, meaning and nuance as a visual artist. The structure and theory I learned as a musician applies directly to my use of pattern, rhythm, lyricality and syncopation in metalwork.

My earliest artwork was inspired by African and Haitian art. Two ideas from this period remain at the core of the work I do now, despite the fact that these ideas have taken me in what appears to be a very different direction.

The first idea is that of encoding meaning in the choice of material, which comes from my study of Bakongo minkisi. The active magical ingredients of minkisi sculptures are often chosen because their visual appearance suggests a desired effect, or because the name of an ingredient (such as lubizu, a grain) suggests through rhyme or pun the desired outcome (zibula, that it may open). The best example of this idea in my own work is The Great Bowl O’ Fire— using a torch to cut flame images into a flammable gas storage tank to create a firebowl which can then be plumbed for gas is a perfect example of how I like materials and ideas to work together.

The second idea is something Robert Farris Thompson alludes to in the essay Rhythmized Textiles in his book Flash of the Spirit. He compares the staggered patterns of Mande textiles and of crazy quilts from the American South to the “off-beat phasing of melodic accents in African and African Amercian music.” That comparison changed everything about the way I work.

In Western art, we typically only consider something to be a pattern when it repeats predictably, like a checkerboard or a picket fence. The idea of a visual pattern as improvisational, erratic and vibrant as a jazz solo seems an entirely different thing, an expression of chaos. But pattern is structure and structure is not always symmetrical. All one need do is look at the world to see constant examples of non-repeating patterns which are nevertheless rhythmic, dynamic and constant: the troughs and peaks of waves, the topology of a region (and it’s relation to the layout of cities or to the distribution of flora and fauna), the paths of migratory birds or patterns of urban decay. From the City Gate project pictured above which uses an accurate street map as a pattern for ironwork, to my Dance sculptures and fences, to my scrap metal abstract fences, all of them are based on this idea of visual pattern based on musical melody and rhythm.

For me, art extends beyond the physical object— Art includes the story, the environment, the experience, and all the adventures getting there. Art is not the stuff we make or buy, art is the way we spend our time, day to day.

The art I make is a byproduct of my true medium, which is living an artful life. What drives me is adventure and curiosity, constant experimentation, new ideas, new experiences, new people, new skills. The most exciting part of my art for me is creating the artist, the person, being exactly who I am, as theater, as an extension of the artwork, as education, as example.

It’s all the same thing in the end— I wake up most days thinking about how I want to change, fix or improve some aspect of the world. And after a couple cups of coffee I get started on it. My speciality is impossibility remediation: if it can’t be done, I’m on it.

ARTISTS STATEMENT —HOW I MAKE ART AND WHY

If my job as an artist is to fill the world with “more things,” I feel it is equally important that I reclaim materials from the waste stream to make space for my work.

Surprise and beauty are a good start, but I expect more and so should you. As an artist and designer, I am committed to sustainable design practices and materials in the following ways:

I work primarily with recycled or re-used materials. This is the best way I know to minimize my impact on natural resources, climate and the environment. I feel creative re-use has the potential to spark new ways of looking at the world… if one thing can be turned into another, what else can we change? Successful recycled art and design encourages creativity in others— it’s alchemical, magical, subversive, and transformative by nature. Read more about my thoughts on recycled art here.

I work primarily with recycled or re-used materials. This is the best way I know to minimize my impact on natural resources, climate and the environment. I feel creative re-use has the potential to spark new ways of looking at the world… if one thing can be turned into another, what else can we change? Successful recycled art and design encourages creativity in others— it’s alchemical, magical, subversive, and transformative by nature. Read more about my thoughts on recycled art here.

I design for permanence. The earliest surviving iron artifacts we’ve found date back to 37,000 years ago… I would like my work to hold to such a standard. Most of my objects will last generations with little or no maintenance. I try to create objects that will never go out of style by drawing from primal metaphor and classical elements of design that speak to what it means to be human and alive.

Because most of my designs are made from recycled material, I shop for supplies at the end-point of consumerism. I see all the manufactured items that are discarded after a short period of use and I design to avoid the mistakes that led to their early demise.

I design for functionality. My work is intended to be useful as well as beautiful. I enjoy the practical aspect of art and feel that engineering is as critical as ingenuity in the creation of solid works of art. Designing for function often means that the most important area to consider is the space around your creation, not the space your art occupies. A chair is the best example— there are thousands of beautiful chairs, but the only comfortable chairs are those designed to fit the form of a relaxed human body. If a work of art is to be valued for centuries, I feel it must consider the most elemental aspects of how people will interact with it.

Story, meaning, music and metaphor matter. I firmly believe in making art that is broadly accessible— work that doesn’t require a formal arts education or a deep grasp of theory to relate to. But I also love creating work that can be appreciated on many layers— As a poet, I learned to use words in a way that had a simple surface meaning, but also revealed deeper connections upon reflection. When choosing materials, forms and methods of construction, my goal is to select the options that combine to reinforce the primary meaning while suggesting alternate reads and new interpretations.

Relaxing makes me tense. If I know exactly how to do something, I feel like it’s already done. Without breaking new ground, there’s no excitement or incentive. Art is more in the doing, than in the done.

I believe that job of the artist is to make new, original and developed work— whether this means inventing something never before seen, or seeing and expressing the commonplace with a freshness that makes the world new again. A new idea is not always shocking (after all, we can reliably and easily predict what will shock people). Rather, I feel the most successful innovations are those which feel familiar almost immediately because even though they didn’t exist yesterday, they so obviously should have. There’s an Arthur Koestler quote I like that describes this, “The more original a discovery, the more obvious it seems afterwards.”

A given piece of art is not a random occurrence… it’s the result of years of study, practice, experimentation and observation. Art is more than an object, a thing, a song, a text or a series of movements— it is the byproduct of creative process, of a devoted way of thinking and living. To create something new, one first must know what exists already. The most valuable thing to learn from art history may be the things that DON’T change— how to see, how to think, how to work.

Creating intricate handmade artwork with industrial tools requires more than just an artistic eye and a skilled hand— Daniel W. Rasmus nails it when he writes “As poets need a large vocabulary to precisely convey their meaning, innovators need a deep vocabulary of science and practice, engineering and management, to construct their innovative wares.”

As I move forward in my creative practice, I find myself ever more fascinated by maximizing the practical application of production (in the sense of producing art with the same attention to detail as producing a feature film). I approach new artistic projects from all angles— first is the concept, the meaning, the story, and the look. But also, the form, the function, the construction, the tooling, the details. Then the numbers, costs, marketing, legal, shipping, etc. All of these aspects have to work if a new idea is successful, but none of them should diminish another. The goal is to produce as much art as possible and reach as many people as I can without ever letting the practical limit the poetic.

THE ZILLION SUM GAME —HOW I ROLL

Not many people have traded art to a bank for real estate. I have. That trade not only had a big effect on the start of my career, it also shaped my philosophy of business going forward. I believe that the only goals worth pursuing are those in which as many people as possible benefit, even those who are not directly involved. I call this philosophy the Zillion Sum Game.

A Zero-Sum Game describes win-lose games such as chess where only one player can win and the other, by default, must lose.

A Non-Zero-Sum Game describes a situation in which it is possible for more than one player to win, although there is no guarantee that all players will come out ahead of where they began. Non-Zero sum is often a win-win situation, but doesn’t neccesarily impact anyone but the players themselves.

As a poet, the awkwardness of the phrase Non-Zero-Sum Game irritated me, and as a business owner, the limitation of its scope felt like it could be expanded. So I coined the phrase Zillion Sum Game.

The Zillion Sum Game describes a situation in which every player wins, but the benefits also extend to as many people as possible, even those who are not playing the game. The goal of the Zillion Sum Game is to further your own goals by positively impacting as many other people as possible, creating a win-win-win situation.

The Zillion Sum Game describes a situation in which every player wins, but the benefits also extend to as many people as possible, even those who are not playing the game. The goal of the Zillion Sum Game is to further your own goals by positively impacting as many other people as possible, creating a win-win-win situation.

Art is especially suited to Zillion Sum Game, because art can impact so many more people than just the artist and patron.

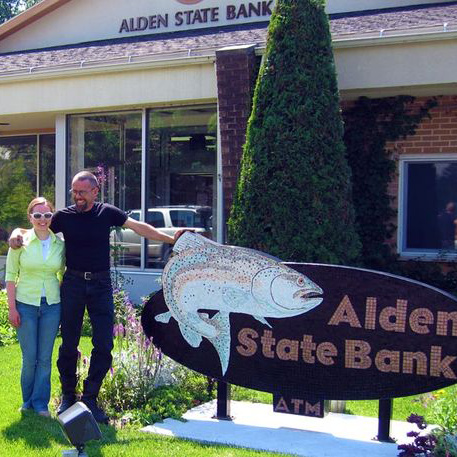

A great example of the Zillion Sum Game in practice is the story of how I traded a mosaic sign (pictured above) as the down payment on a home and studio.

In 2004 I was leasing a foreclosed convenience store and house with an option to buy. It was a harsh winter, without the usual thaws, and due to heavy build up of snow my studio building collapsed while I stood on the roof shoveling. I rode the building to the ground. The building, some artwork and some expensive tools were completely destroyed, but I was unharmed… aside from having to live without heat, running water or a stove for three months because the natural gas line into the house had been severed in the collapse.

When the bank came out to assess the damage, they were impressed by my art and suggested I make a commissioned sign as the down payment on the remaining two buildings. I don’t think the deal would have happened without the disaster… They didn’t want to take a loss on the property (or hold it) and I was willing to take it on at the cost of the mortgage before the building fell. The deal was a win for the bank, a win for me and a win for the people who enjoyed the public art of the new sign.